-He who makes a beast of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man –

Samuel Johnson, (used as an epigraph to Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas)

Lessico Animale (Animal Lexicon) is a complex exploration and investigation of the relationship between Man and Animality, an art rite in which the artist intends to unveil the authentic essence of the human being, taking him back to his instinctive and animalistic origins, overcoming the taboos and cultural superstructures that keep him away from them.”

from Yuval Avital’s website (http://www.yuvalavital.com/lessico-animale-prologo)

The theme of Animal Lexicon: Prologue, of man’s “instinctive and animalistic origins”, and our paradoxical fear of, and attraction to, the idea of giving in to our primal side, our “authentic essence”, is as old as Western culture. There are the lustful satyrs of Greek mythology – part-man, part-horse -threat to nymphs and women, and on the female side, the Maenads or Bacchae, women of animalistic nature who dressed in fawn skins and practiced weird rites in the mountains and woods – and who tear Orpheus, the poet, to pieces. In the Odyssey, there is the episode of Circe, who turned Odysseus’s men into swine with the use of magic and wine (but with the implication that the men fall prey to their own weakness). The Bible is full of warnings about the pitfalls of giving reign to one’s animalistic side. In Victorian literature we have the inner conflicts of civilized/savage man in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886) and Emile Zola’s La Bête humaine/The Human Beast (1890), but also paradoxically a fascination with – and idealisation of – “Arcadian” life (including those naughty nymphs and satyrs) in the poetry and painting of the Romantics and Pre-Raphaelites.

From the twentieth century onwards the theme has continually been explored in various strata of “high” and popular culture, and it’s interesting how the “animalistic” in man can take the form of either pitiful wretchedness, or by contrast, a fearsome energy: from Adolph Verloc in Conrad’s The Secret Agent (1907), who like one of Odysseus’s men in the Circe episode has fallen prey to indolence and baseness (but irredeemably- no magic charms here to reverse it), is “burly in a fat-pig style”, and is described as “the animal” by an embassy attaché, to the infinitely more desirable and untameable Valentine Xavier, a wandering musician decked out in a snake-skin jacket who projects a primal sexual energy almost despite himself, in Tennessee Williams’ play Orpheus Descending (1957); from Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast (1946) to the Disney version (1991); from the evocation of animalistic transformation and Dionysian revelry in the songs of The Doors (1967-1970) to the rapid dissolution of Raoul Duke and Dr Gonzo via copious amounts of drugs and booze, declining over the course of a week-long reporting assignment into almost grotesque creatures (amplified by Ralph Steadman’s illustrations) in Hunter S. Thompson’s cult novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971).

In the international television advertising campaign for Dior’s men’s fragrance “Sauvage” (2019), Johnny Depp abandons the confines of “civilized” Los Angeles for a road trip to the desert, where he can exercise (not exorcise) his authentic “savage” self, through an electric guitar which apparently needs no electrical supply, free and alone, except for a few wolves, who recognise a kindred spirit (perhaps their “spirit human”?) – or perhaps they’re attracted to his scent, or maybe it’s Dior’s scent. What is evident, even from this small collation of examples of the theme of “man’s animal nature” in Western culture across time, is our paradoxical horror of, and attraction to, the idea of “giving in” to it.

It was in the city of Parma on a Wednesday afternoon (7 September, 2022) that I stumbled across the exhibition by Yuval Avital at the APE (Arts Performance Events) Parma Museum.

I was in Parma for a week on a teaching project. The evening before, I had had a few too many glasses of wine at a bar and got into a stupid argument on an insignificant point with a colleague I barely knew. I did not feel guilty later, as I was certain that I had been dealing with a man who got prickly when juiced, and relished an argument… Nonetheless, I was annoyed at myself for allowing myself to get drawn in, and consequently having a wasted evening – or more precisely, a soured wasted evening, as opposed to the enjoyable kind.

I realised that once again I was falling into the exquisite trap of too much alcohol and the indiscriminate search for company, to stave off a confrontation with ennui, aimlessness, loneliness, and other uncomfortable feelings. The following morning, I decided that I would forsake the evening socials for an exploration of the museums, theatres, and galleries of Parma for the following three afternoons- a kind of project for myself, which if not in any way productive, would at least be a more cerebral and independent manner of time-wasting.

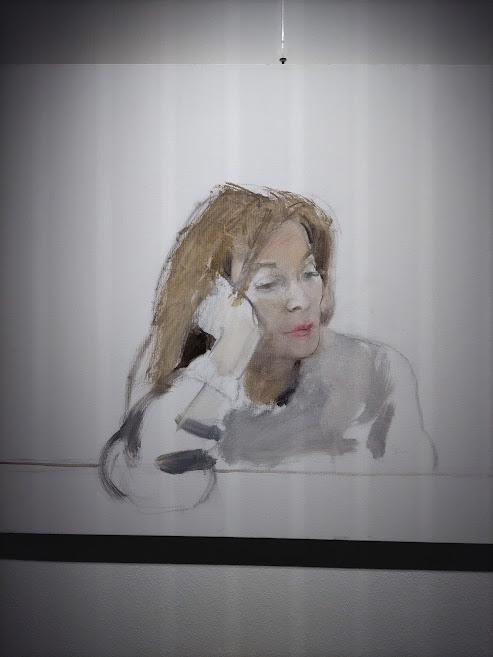

Consequently, I came to the APE museum, I suppose, looking to be “elevated” by culture. The top floor exhibition couldn’t have been more “elevated”; an exhibition of the portrait paintings of father and son artists Renato and Luca Vernizzi. Both artists are highly regarded and in fact the work of the father, Renato Vernizzi (1904-1972) is situated there permanently. Despite differences in style between the two artists, the exhibition is one near-seamless exhibition of graceful portraits of the pensive middle class, many of whom are, or were, important cultural personages in Parma, from the 1950s to the present. I could appreciate the formidable artistry but, walking through the rooms, the portraits redoubled my Prufrockian despondency: no one in here, including me, would seem to “dare to eat a peach” without hedging about it.

If the top floor of the APE reflected the life of the mind, of abstract thought, of lives devoted to the various fields that maintain and advance civilization, then the ground floor was its exact opposite – a reflection of the primal, the irrational, the primitive and ritualistic aspects of man, his “authentic essence”, as the artist’s text defines it. The exhibition is composed of photographs, sound loops, sculpture, preliminary sketches, murals, and at the centre of this, a video film of a performance piece Avital created with nineteen actors from the Casa degli Artisti del Teatro Due in Parma. The video projection is divided into two parts – the first, encountered in the first of the rooms, which are arranged in a way to feel labyrinthine or cavernous, shows the process of the actors preparing for the performance, described here (from the artists’s website):

Every day the actors enter a space with a strong symbolic value, the Transformation Room, organised along the cardinal points, where from dawn to dusk their mutation from humans to animals gradually takes place. Initially they wear a blue uniform that gradually, as the animal state emerges, is removed and replaced by body painting made by Avital himself on their bodies with natural pigments. Moving around a centre of living earth, the performers embark on a journey of initiation: at dawn they wake up as men, at midday they enter into a process of hybridisation and only after sunset does the transformation into animals take place. As animals, they spend the night until the following dawn, and thus cyclically repeat the six days of work.

Some details are hazy – “as animals they spend the night until the following dawn” – we must assume that they slept at night, or they would not have maintained the required energy over the six days, but they slept “as animals” – does this mean they did not sleep in their beds but somewhere in the performance space? Did they sleep still adorned in body painting? I do not know, yet it would not surprise me if this were the case, because the recorded performance of the group – the second part of the projection, presented in a deeper cavern of the exhibition space – is wholly physical and without language (as befits animals) and is persuasive, disturbing, and abrasively erotic.

It seemed then that it was not the cerebral but the primal type of art experience that was speaking to my starved soul that day (starved soul – the body was being very well nourished in Parma). Avital’s Animal Lexicon seems to be part of a lineage of art intended to make you feel first, and think second: it’s primal, physical, dynamic: it is relatable to the dithyramb – the dance of the chorus in ancient Greek theatres, in celebration of Dionysius, but also to the shocks of a well-executed horror film. Animal Lexicon is, as they would have called it in the era of The Doors, “a trip”, and if this exhibition comes your way, you should, to use Hunter S. Thompson’s famous maxim, “Buy the ticket, take the ride.”